J A M E S B L U E AND M E

— BY RICHARD BLUE —

(reminiscences compiled and edited by Richard Herskowitz from emails sent by Richard Blue)

Working on my brother’s materials has been exciting, and it forced me to come to grips with my own understanding of this complex, often tormented, frequently joyous and exuberant man. He was special.

A bit about me, and James. I am/was about six years younger. I did some time at the U of Oregon but finished up at Portland State (my degree was in Political Science) after returning from military service. I was lucky enough to get a full fellowship to get my PhD at Claremont in Government and International Relations. I went on to academia and then USAID and other international work.

We fought like animals growing up, but by the time he was in college and I was in high school, we became good friends and very close. My brother spent a lot of time with me discussing several films, including A Few Notes on Our Food Problem (I had a strong interest in Indian agriculture at the time), and two which never got made; one was on the American Revolution (in retrospect, it was a kind of Olive Trees of Justice re-set in North Carolina in the 1770s), and the other was called the “Family Film”…on which a very young Gill Dennis[1] spent a year with James interviewing and recording all the Blue family relatives still alive from the 19th century (this is around 1964/5).

As he was developing the idea of a “family” film, he would come up to Minnesota and we would talk (and drink Scotch) well into the night. [Tape recordings in the James Blue archive] include interviews with elderly surviving relatives and with our father about what life was like on a farm in southern Missouri, and what life became for the Blue boys who all left to go to the big city (shades of Dreiser here). James wanted to use the small story of the Blue family to tell the big story of America’s transformation from a rural, largely agricultural country to the 20th century urban industrial country it became…a process that started, of course, in the Civil War and latter half of the 19th century. I regret that we could never quite get this one into shape.

Anyway, lots of stories to tell [about our family roots].

I’ll start with my Mother’s Mother, Grandma Fannie (Willis) McConnell. Her Dad ran an Indian Trading Post in Stillwell, Oklahoma while it was still a territory. She met George McConnell, who worked for her father, and married. They had six children, two of whom died. One who lived was my mother, Maude Pauline (McConnell) Blue.

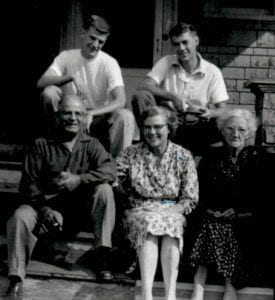

Grandma McConnell was raised a Baptist but was not overly impressed with the church. She and George “ran” the Cherokee Strip, when Indian lands were opened up for white settlers in the 1890s. George was a carpenter by trade but was also a leader who believed in the rights of the working man and woman, becoming the President of the Bartlesville, Oklahoma Council of Trade Unions around 1916. His platform advocated elimination of prison labor, elimination of child labor under age 16, and, remarkably, equal pay for equal work for women and men. Both were pioneers in their own way. They moved eventually to Tulsa, Oklahoma where Jim Blue and I were born and where my brother and I spent several summers with them, chasing ice wagons and playing in the dusty streets and neighborhoods of a growing city.

We left Tulsa in late 1942 for a new life in Portland, Oregon. George McConnell died and Fannie came to live with us in the late 1940s. She was mainly a tough and wise lady who soldiered on, and on…dying in our rose garden one June at age 89. I loved her and benefitted from her frequent intercession with my Mom about disciplining me.

Jim, being older, knew her well, and benefitted from her practical wisdom, love, and protection from our over-anxious Mother who feared Jim was “going off the rails” as a rebellious young teenager.

Mom was one of 4 surviving children…she was ambitious, wanted to be a teacher, went to Normal school, but dropped out and finished at a business/secretarial training school after which she got a job in Tulsa, met my Dad, married in the 1920s, and did “all the right things” of a middle class Oklahoma existence.

Always considering herself a genteel and proper Christian lady, my mother inherited a strict Puritan code of behavior and morals from her mother. Mom was a beautiful woman who lacked a sense of humor and had difficulty showing physical affection and empathy. (She once said that sex was only for having children. By 1950s, she and my dad were in separate bedrooms). She was ambitious and not afraid to strike out on her own, as demonstrated by the fact that she was a full-time female employee in an architectural firm full of men in the 1920s. Then, after marriage and the Depression, as often happens, she projected that ambition onto Jim after her own efforts to go to college ended due to lack of funds.

Dad, a farm boy from Missouri, was artistic, musical, loved people and their stories, and loved to put on shows, could do any kind of home renovation, and had a love for poetry and song. He worked for an architect as a draftsman and architectural renderer (Lee Shumway) in Tulsa, met Mom, built her a house and they had James Blue in 1930, just after Wall Street collapsed. By 1931, Shumway closed their doors.

For four years, my Dad and Mom survived by moving from one house to another, fixing it up and moving on. It was grim, and Dad had a nervous breakdown. [In audiotapes recorded by James], Dad recalls the beginning of his “breakdown,” which started the day he got a phone call telling him he had a job with the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (Roosevelt’s HOLC)), and subsequent spells when he would start bawling inexplicably. This lasted for about a year and occurred 1934-36, about the time I was born. We both grew up with our Dad’s stories about those awful years, and I think those stories did influence our later political thinking, for me probably more than James.

We became Roosevelt Democrats by osmosis from those stories…even as our parents became more and more conservative. My Dad was saved by the New Deal by getting a job with the HOLC, a forerunner to the Federal Housing Authority. We knew from him that government could do good things, and that just letting free market capitalism do its thing was not the way to go. Roosevelt’s commitment and leadership to American rebirth more than any other single influence helped shape our political views, because they fit so well with our Dad’s survival and emergence from the horrible years of the Depression.

Mom became afraid, and God-Fearing. She never lost her middle-class nice person sensibilities, but her religious faith shifted more and more toward a conservative brand of Christianity. When we moved to Oregon in 1942, we belonged to the Mallory Avenue Christian Church…but Mom thought the Pastor way too liberal and the church belonged to the National Council of Churches, another suspect “liberal” body. She left the congregation, joining the St. John’s Christian church (independent), where they stayed until both died. I remember going to Sunday School, doing the baptism and all the rest, and I suspect James went through the same. By the time of about the 7th or 8th grade, we were both rebelling, each in our time, against “going to church”.

The Depression and her efforts to avoid becoming “Poor White Trash” took its toll. Mother became increasingly fearful. Fear of change, fear of “moral decay”, fear of “liberalism” (read socialism, read communism) became the dominant themes, along with finding a way to remain “respectable.” In this value system, there wasn’t much room for non-conformity. As the cold war developed after WWII, she became convinced that communism was a clear and present danger, and gave money to right wing groups, including the John Birch Society, a forerunner of many of the fear groups out there today. And clearly it was Russia and the commies who were behind the protests of the civil rights movement, and later the Free Speech and Anti-Vietnam war protests. She said black people were becoming “too uppity”, were lazy and didn’t know their place. She was a “genteel racist” to the core.

As rebellious young people growing up in this environment, James and I emotionally were being prepared to follow different values, different paths. Whatever it was, it was not going to be what our Mom came to represent: bigotry, fear, rigidity, suppression of sexuality, and all the rest. We knew we wanted something different, but we embarked on uncharted waters.

I hate to think of what our family life would have been had it not been for my father’s love of funny stories, his creative imagination and talent. Dad was always engaging Jim in little shows when Jim was in Scouts, and during visits from dad’s equally hammy brothers, would dress up and put on skits for Jim to film. Dad loved American history, had a strong visual acuity, an almost photographic memory, and could recite long streams of romantic English poetry he had learned in high school, which he never finished.

Our dad was a romantic at heart, often sentimental, sometimes maudlin. He was a man who needed affection, didn’t get much from Mom, and sublimated it all into his little “shows”, his art, and his reconstruction of our Portland home into something that looked like a Swiss Chalet…right there on old Simpson Street in North Portland. Like my Grandfather James William Blue’s response to my moralistic and opinionated Grandmother Rachel Ann, Harry Blue was the antidote to my mother’s stern morality and mid-western conformity. To her credit, very much like Rachel Ann, my mother was ambitious for her children, and pushed us to go on to college, ambitions that were lacking in my dad…who never finished high school.

When we moved to Portland in 1942, Jim was 12, entering adolescence, desperate to find his own identity, which to Mother was simply rebelliousness, stubborn and willful disobedience, and failure to live up to her increasingly rigid and humorless standards. She actually bought a buggy whip to use on Jim when he fought back.

Jim was very unhappy the first two years or so in Portland. He had bad acne, was awkward and not athletic, had a big gap in his teeth and wore braces, was unsure around girls, and hated the fact that we didn’t have the kind of clothing kids were wearing in Portland. He wanted to be part of a group at Jefferson High School but didn’t know how to do this. My father recounted later that Jim said, “I hate myself!” Because both our parents were working, Jim was home alone with me from 3 to 6 pm, and regularly taunted me; taunts which resulted in fights that could have ended with serious injuries. I was afraid of him, did not want to be around him, and tried to stay away as much as possible.

Two teachers at Jefferson High “saved” Jim Blue. Ms. Campbell, Latin, and Ms. Melba Sparks, Drama, found him, nurtured his talent, and got him into groups that shared his non-conformity. They gave him an outlet for his creativity and imagination…and the approving feedback he craved and could not get from my mother. He found a means [through theater and film], to realize his talents and creative urges, and to begin to show off his own sense of humor, largely the same as our dad’s. Unlike his more serious and nuanced lyricism, his sense of humor was largely shaped by and in the same mode as Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. My dad adored Buster Keaton’s films, took Jim to watch them. Jim loved slapstick and parody. His early films like Hamlet and The Silver Spur were largely shaped by his rather goofy sense of humor.

The sources of my brother James’ creativity are clearly his inheritance and support from our father, Harry B. Blue…an uneducated farm boy [with] a strong sense of humor and empathy, an un-taught artist, a storyteller, a frustrated showman, a musical talent, and an incurable romantic, a man who put duty to his wife and family ahead of everything else.

The major factor in Jim’s rebellious and anti-authoritarian personality has to do with our Mother. She literally tried to beat his rebelliousness and unhappiness out of him as a teenager.

Gill Dennis, who knew James well, said to me: “It was all about his Mother.” Later in his life, my mother reveled in his success, was proud of him, and spoke glowingly about her son’s accomplishments to others. For his part, Jim spent a lot of money, time and effort trying to please his mother, and to assuage his own sense of guilt about his unruly and rebellious relationship with her during his teenage years.

But his need for recognition and, indeed, adulation, never left him. I think it came from his own sense of alienation, an alienation that started when we moved from Tulsa to Portland, and he was rejected by all the “popular” cliques and activities. He learned early to get gratification from “the crowd” through showmanship, starting with magic shows, puppet shows, early movies, radio, theater, and on and on. Because of his early successes, his good looks (the rock star), his intelligence and his charismatic persona, he was able to meet this need for attention and approval without having to work too hard for it.

At the same time, he worried about looking good, having the right clothes, getting praise from critics and students, etc. I think Colin Young[2] once said, “his problem was he couldn’t say no…” to an invitation to speak. His diaries reveal that he was a procrastinator, almost never organized his talks or his classroom teaching, had trouble with the daily routines of bill paying, and was tormented by his inability to initiate his own projects, rather than reacting and responding to the invitations and initiatives of others. The conflict between his need for attention and “love”, and his desire to produce great film was a constant source of inner torment and self-doubt throughout his life.

So the interweaving of threads, Grandpa McConnell’s union liberalism, our Grandma’s pioneer toughness and pragmatism, my Dad’s artistic and romantic talents and sensibilities, the trauma of the Great Depression, and my Mom’s increasing adherence to conservative Christianity and rampant fear of communism in the cold war, along with James’ own desire to be recognized, and our adolescent (and not uncommon) rebellion against all that our dominant parent, MOM, believed in made up part of the material, along with our particular talents, that produced the fabric of our lives.

I left out the profound influence that his experience in France at IDHEC, and later in Algeria, had on him. He had to confront Marxist critiques of everything American, for which he lacked the education and training to contest.

Once, I was working at my base in Germany late in 1956. Late at night I got a call from the guard house. “There is some hippy looking guy here in an old army jacket who says he’s your brother”. Sure enough. Jim wanted to talk to me about Marxist Leninist theories and find books in the base library about same. I told him a small Army base was not the place to look for objective analysis of Marx’s writings. Why all the fuss? “I’m being beaten up about American capitalism and imperialism by all my friends at IDHEC and I don’t know how to defend America!” He was very troubled by this, enough to come all the way from Paris to see me.

He loved France, but he was a Midwestern born American, and wanted to understand his own land. France and the family of his great IDHEC friend, James Dormeyer, had other effects, such as helping him to shed his Puritan upbringing, to realize that one could have a family, the Dormeyers, who were everyday people, but rich in stories, long family dinners with great food and wine, and an obvious enjoyment of life that was missing in our own upbringing.

Jim wasn’t a political person, or an “activist” for social justice in the way my son, Dan, or my grandson, Finnigan Barkley Hawley-Blue are. We both did not become “activists” in the normal sense of that word. James had a strong commitment to using film to understand and film technology to empower people to explain their own stories. I became a social scientist and evaluator. We both ended up looking at the world through a lens, and a somewhat detached position.

Jim’s passion was film, the visual image, and the power of storytelling through film. He was a fine actor, a gifted illustrator and artist, but it was the moving visual image that captivated his interest. He saw film as a “democratic” art form…which would allow the “stories” to come out and be made compelling whatever the source: rich, poor, elite, bottom of the social ladder, black, Latino/a, whatever. He was deeply committed to “democratic participatory” cinema…cinema “of the people, by the people and for the people.” I think this belief also influenced his interest in using “non-actors” in film making, a subject about which he came to know more than almost anyone in his profession.

Motivated by his desire to find, record and tell stories with film, he had three fundamental inclinations: One, to respect every person’s life experience, whether that person was a real estate developer on the 19th floor of a Houston tower, or a black woman sitting on the porch of her dilapidated row house in the 4th ward. They all had a story to tell. Two: empathy…he had an ability to put himself into the shoes of people who interested him, especially his students and the subjects of his films. Third: had he not been a totally artistic talent in love with film making, he would have been an excellent anthropologist or sociologist…he had an almost desperate need to “understand” and “get the explanations right, true, nuanced, and balanced.” He was never satisfied with easy answers, conventional wisdom, or the ideological explanation…. He never started a film with a judgmental hypothesis that was to be proven in the film.

The other main dimension of Jim’s life, and contribution, was as educator and mentor. Because of his compelling personality and his serious in-depth knowledge of cinema and how to approach the challenge of good storytelling, he made an impact, often a profound one, on many young people who later became cinema professionals…whether at UCLA, AFI, Rice, or through lectures in America, Canada and Europe. And he was proud of his accomplishments at Rice University, despite criticism from [his wife] Janice Blue, who rightly told him he wasn’t accomplishing anything as a filmmaker at Rice. This criticism hurt him, and in some ways, he recognized the truth in the criticism…again, the conflict between his need for attention and respect which he got from teaching, and his need to make films was in play throughout the Rice period.[3]

There are two great and illustrative scenes in the last days of his life when he was dying of cancer. One takes place in a small seminar room in a London hospital, a Victorian pile of a building, where Jim, at their invitation, enthralls a group of young medical interns by talking about what it means to be told you are dying and will be dead in six weeks. The other is in the dining room in his house on North Mariner street in Buffalo, NY, where Jim has arrived, tired from his long journey from London with me. Jim is sitting at a round oak table filled with his students and colleagues from the Center for Media Study, all talking about film, their problems, and laughing at jokes, drinking wine…and saying goodbye. Jim presides, pale and tired, but presides nevertheless. The group leaves about midnight. Jim goes into the Roswell-Park hospital the next morning. He dies three days later.

[1] Gill Dennis collaborated with James Blue on A Few Notes on our Food Problem, and became a screenwriter best known for Walk the Line.

[2] Colin Young chaired the UCLA Film School when James Blue taught there, and he and Blue both lectured in each other’s film programs at Rice University and the National Film School in London.

[3] Editor’s note: James Blue made significant works (the ethnographic film Kenya Boran and the collaborative, community media series Who Killed Fourth Ward? and The Invisible City) while at Rice. However, during that period of his life, he turned away, with some regret and self-doubt, from the feature film career in which George Stevens, Jr. and others thought he could have excelled.